Sea Grant-funded Research: Sowing seeds of restoration

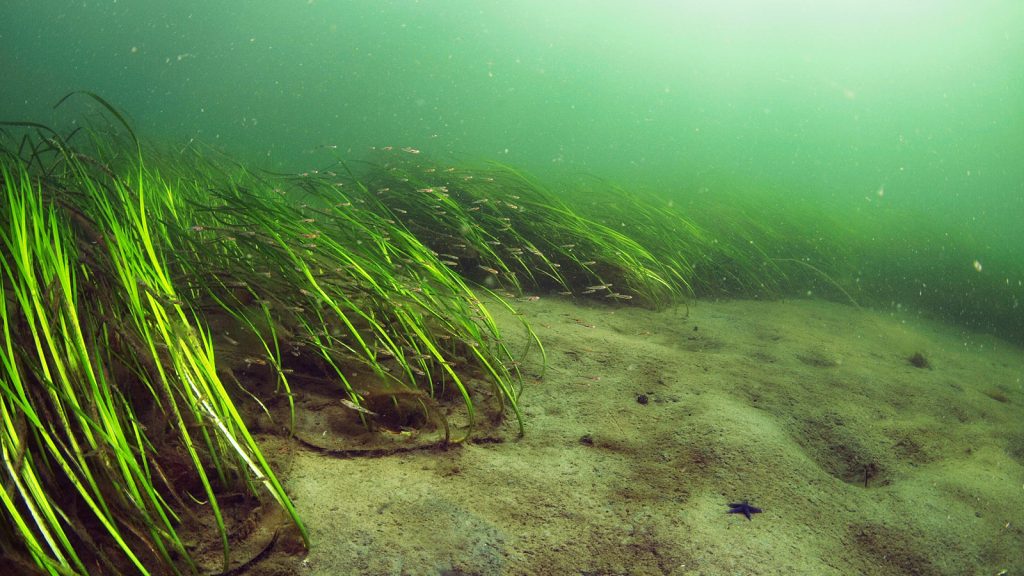

They’ve been called the nurseries of the coastal waters. Eelgrass meadows are crucial to the health of coastal ecosystems and the planet, providing essential habitat for marine life. In addition, they stabilize shorelines, improve water quality, and even contribute to climate change mitigation by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide.

But across the globe, the planet is losing an astounding two acres – about two football fields – of seagrass every hour. Here in Massachusetts, we've lost about 50 percent of our eelgrass since the 1990s due to nutrient pollution, degraded habitat from boating and fishing activities, rising ocean temperatures, and disease.

Eelgrass restoration efforts have been undertaken to combat the loss of this vital habitat. Some have been required as mitigation in direct response to impacts from construction projects, and more recently, there have been a dozen or so eelgrass restoration efforts unrelated to mitigation. Most of these have been unsuccessful, with restored areas totaling around 30 acres.

“Compared to the loss of approximately twenty-thousand acres since the 1990s, we are nowhere near where we need to be,” says Jill Carr, a coastal scientist at MassBays National Estuary Partnership and UMass Boston. With funding from WHOI Sea Grant, Carr and her partners Forest Schenck, with the Mass. Division of Marine Fisheries, and Alison Frye with Salem Sound Coast Watch, are exploring new methods for restoring eelgrass meadows.

Traditionally, restoration efforts have used a very labor-intensive method transplanting adult shoot plugs from one site to another. Carr’s team is focused more on seed-based approaches, working to understand the necessary components to successfully grow eelgrass on a large scale: Which seeds stand the best chance of growing into flourishing eelgrass meadows along our coasts? When is the right time to collect the seeds from donor meadows? What are the best practices for seed processing, handling and storage?

The project aims to fill some of these knowledge gaps through activities such as:

• Field surveys using SCUBA divers to assess the density of eelgrass meadows. The divers are also harvesting some of the eelgrass flowers to chart the timing and conditions for when those seeds are mature.

• Data modeling to predict the optimal timing to collect seed in the field to hopefully increase the efficiency of restoration efforts.

• Seed-viability testing to better understand restoration outcomes. This includes measuring the speed or “fall velocity” of each seed as it drops through a test tube of water. A heavier seed is a more viable seed.

• Field germination experiments where local and non-local seeds have been planted to find out what percentage of seeds will germinate. “It’s important for restoration projects to take this percentage into account and plan accordingly for it,” Carr says.

With the project now in its second year, the team is focused on looking at the impacts of harvesting on a meadow and assessing the role of temperature on the stages and timing of seed development to create a forecast model for eelgrass maturation.

“The greatest opportunities for restorations are in places where existing eelgrass can be supplemented, and in places where eelgrass has been totally lost, but where water quality and other stressors have since improved,” says Carr.

The project will culminate in the development of a best practices guide which will be shared with regulators and restoration practitioners to improve their efforts into the future.