Culturing Kelp on Cape Cod

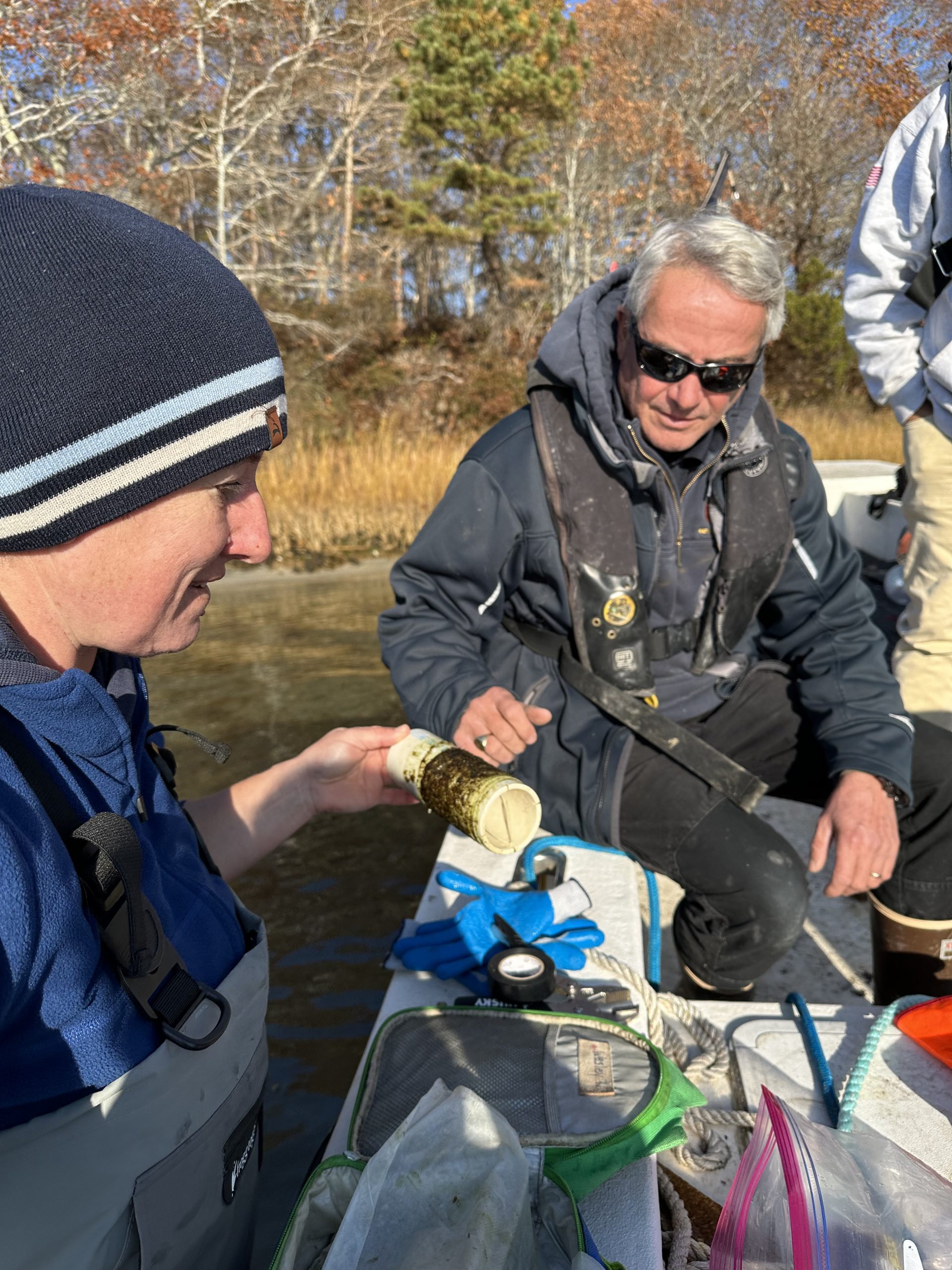

Rachel Hutchinson splashed through a foot of ice cold water in her waders to climb into a 17-foot skiff. Setting down a cooler full of seaweed and plastic bags of scissors, tape and data sensors, she pulled the black hat of her raincoat further down her forehead. A steady patter of rain made small ripples in the water as Josh Reitsma pushed the boat a foot deeper, pulled himself aboard, and fired up the engine to steer the boat into a Yarmouth embayment.

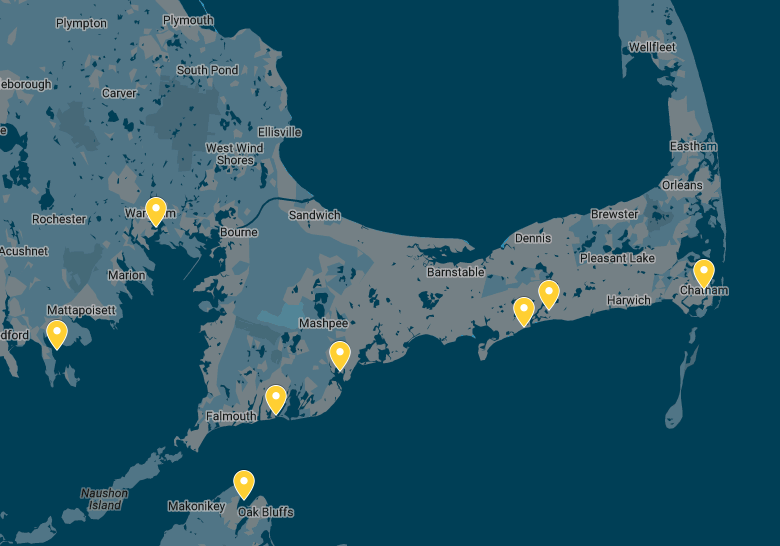

Hutchinson, Reitsma, and Abigail Archer launched an experiment to explore how well sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima) grows on Cape Cod – if at all – by planting kelp in eight different locations across Cape Cod in November 2023 and tracking its growth through the winter season. The three scientists represent both WHOI Sea Grant and Barnstable County as Cape Cod Cooperative Extension agents in their work on fisheries and aquaculture.

“There’s a lot of interest in kelp for different reasons, though the economics of kelp aquaculture is unpredictable right now,” Reitsma said. “But the reality is, you have to be able to physically grow it. And if it's not growing well, why not? That's the crux of this project.”

This pilot study will collect preliminary data to explore why kelp has not typically fared well in attempts to farm it on Cape Cod. The team collaborated with local aquaculture farmers to identify and co-locate the kelp for this study with existing aquaculture farms, either shellfish or kelp.

Shellfish farmers are interested in kelp because its growing season is opposite that of oysters and quahogs, Hutchinson said. Kelp thrives during the winter and is harvested in April, while oysters and quahogs are planted in the spring and grow through the warmer months of the year, she explained.

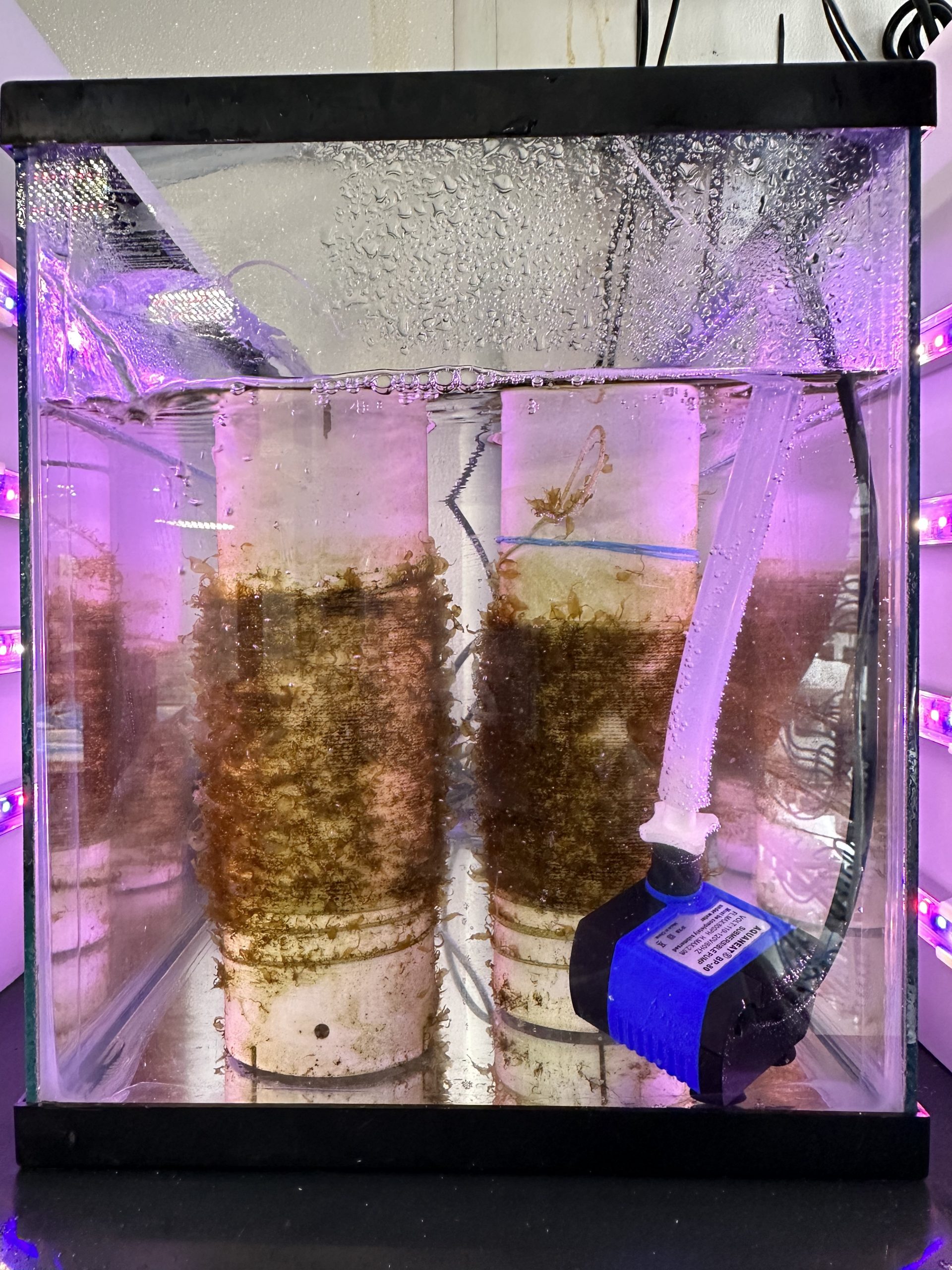

Kelp can grow rapidly during winter's cold months. These photos were taken at the Falmouth site two weeks apart.

“A lot of the shellfish growers look at kelp as a potential alternative crop, but they have questions as to how it might work on their existing sites,” Reitsma said.

Half the kelp sites are located in shallow, nutrient-rich coastal embayments, while others in deeper waters where nutrients are likely more diluted. The team can walk out to the shallow sites, 2- to 3-feet deep during low tide, but need a boat to access the deep sites.

“The hypothesis of this experiment is that kelp is nutrient-limited in offshore waters, so it'll grow more slowly out there,” Reitsma said. “But in these inshore waters, where we can hopefully demonstrate that there is more nutrient available to the kelp, the plants will grow a bit faster.”

Every four to six weeks from November through March, the team monitored kelp growth and took water samples to measure dissolved inorganic nitrogen at each site. After harvesting the kelp in April, the scientists will assess how nutrient availability impacted the kelp’s growth.

“If we can show that it grows in the inshore waters,” Hutchinson said, “it opens up the opportunities for a lot more people to enter kelp farming.” Kelp farming in shallow waters has been successful in other locations in the northeast U.S. Growing kelp in deep water can be more resource intensive and therefore prohibitive, she explained.

Halfway through the experiment, Hutchinson, Reitsma and Archer have noted that the kelp grew in some locations, but not too well overall. While confirming what previous attempts at kelp farming has shown, that kelp growth on Cape Cod appears to have limitations, the team has more questions now – such is science!