Meet the Intern: My journey into the world of lobster

By Kiran Johnson

I am allergic to lobster. I grew up in Chicago, and deep dish pizza is our pride and joy, not lobster rolls. When I moved to Boston to study journalism and environmental science at Northeastern University, my college-student budget prioritized coffee over seafood dining experiences. And so it was fitting, then, that I decided to spend five months communicating lobster science.

In January, I arrived at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) for an internship with the Sea Grant program focused on sharing science information from research under the American Lobster Initiative (ALI). The initiative involves 39 research projects about the future of lobster and the fishery in the face of economic, regulatory and environmental changes. My three target audiences for this communications effort were lobstermen, seafood industry workers, and journalists. I remember thinking, “Who am I to try to inform lobster fishermen and seafood industry workers about lobster?”

Feeling out of my depth is not new. Previous science writing experiences had me deep diving into hyper-specific topics, such as salt marsh ecology, oyster evolution and the bi-directional relationship between social media algorithms and body image. Working outdoors in different environments, from the alpine ecosystems in Colorado to the golden shrub-and-grass speckled mountains in Morocco, has pushed me to quickly learn about local ecologies.

Figuring out what questions to ask to unlock the secrets of each new environment or scientific subject is like a maze, and choosing the right path rewards me with a new piece of information.

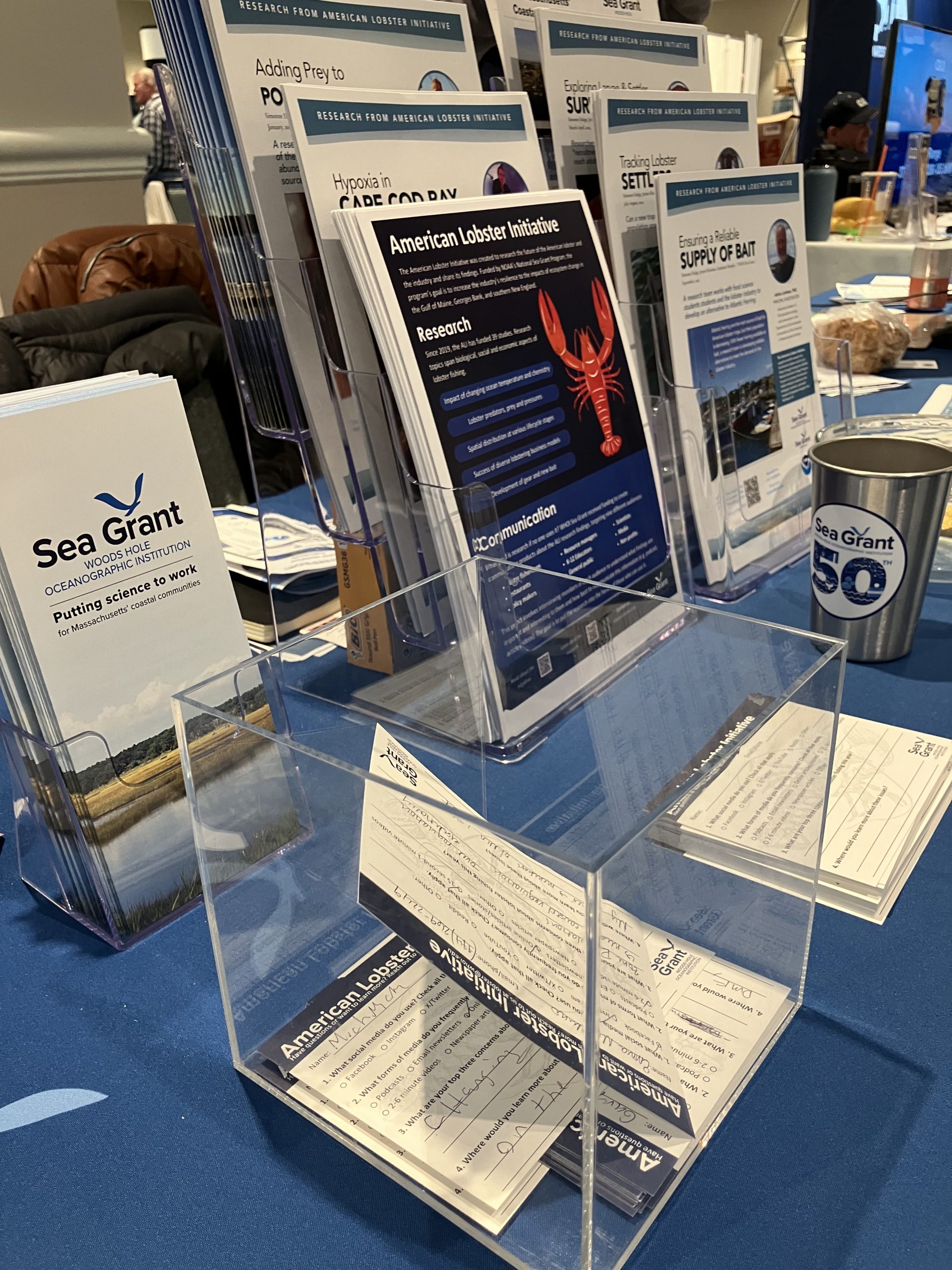

My first step into lobster fishing and science, other than a computer screen with too many lobster-related tabs open, was at the Massachusetts Lobstermen’s Association’s (MLA) annual meeting at a hotel in Hyannis. I had two goals: to understand what information from ALI research projects lobstermen might find useful and, second, how to share this information effectively with them.

To gather my data, I designed a postcard-sized survey that I asked lobster fishermen to fill out at the MLA meeting. The survey was intentionally short to counter the fatigue that many lobstermen feel from completing countless research and industry surveys over the years . I followed up with willing lobstermen for an in-depth interview in the weeks following the meeting to gain more insight.

My many laps around the MLA conference room yielded a range of conversations and reactions from lobster fishermen: some were surprisingly emotional about the condition of the fishery, leaving me with watery eyes; others were skeptical of my WHOI name tag and stack of surveys, given the complex relationship between scientists and lobstermen (I found that carrying chocolate to offer people helped with this); and many lobstermen were excited about my newness to and curiosity of the fishery.

" I learned that being a lobster fisherman is more than a job: It’s community, tradition, connection to the ocean and a schedule with a varying number of watery sunrises and black, star-specked skies each week." - Kiran Johnson

Empathy for how lobstering is so prominent and personal in fishermen’s lives guided my way through the maze of this new world. I learned that being a lobster fisherman is more than a job. It’s community, tradition, connection to the ocean, and a schedule with a varying number of watery sunrises and black, star-specked skies each week. The question, “What about lobster do you want to know more about?” couldn’t be resolved without bringing up questions like how warming waters affect lobster fishing, what challenges lobstermen feel they are facing regarding regulatory and economic changes, and worries about the fishery’s future.

Thirty-one surveys and 12 follow-up phone interviews later, I compiled all I learned into a paper for future ALI communicators to draw from. Based on my findings, I am focusing my own content creation efforts on an ALI project that investigates lobster stress in relation to the construction of offshore wind farms.

WHOI researcher Andria Salas uses recordings, collected by fishermen with hydrophones strapped into lobster traps they put in the ocean, to understand how construction sounds affect lobster heart rate, an indicator of stress. Salas uses a self-crafted saddle, made from a snorkel mouthpiece and Velcro, to attach a finger-length, cylindrical heart rate monitor to the lobster she is testing.

I visited the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation (CFRF) in Rhode Island to hear from fishermen captains on working with the hydrophones and the importance of this research project to them, with multiple wind farms currently being constructed in the waters off of Rhode Island. Mike Long, CFRF senior research biologist, told me about the value of this type of collaborative research in the world of science.

After hearing all these different perspectives on lobster and specific issues in the fishery, I’m still allergic, but I can tell you that young lobster larvae drift in the ocean’s current until they are able to swim, that lobster may live up to 100 years, and that they have two different claws – one for crushing and one for tearing. I can even make a lobster fall asleep by petting the spot between its eyes.