Restoring Bogs and Preserving Southeastern Massachusetts’ Cranberry Heritage: Woods Hole Funded Project Impacts Future of Iconic Industry in Southeastern Massachusetts

This time of year cranberry bogs in southeastern Massachusetts are something straight out of New England central casting: flooded pools with floating berries gathered in tight crimson circles, ready to be vacuumed into trucks by wader-clad workers slowly moving through often chest-high water.

This iconic autumn image certainly helps when marketing cranberries, but there’s a greater story behind our region’s cranberry industry. Perhaps unknown to many consumers, cranberry bogs play a crucial role in the health of the watersheds in which they are located, especially when it comes to the amount of nitrogen entering an estuary. A bog’s age, proximity to an estuary and the growing methods all play a part in the bog’s impact on the environment.

A recent Woods Hole Sea Grant-funded research project into our region’s cranberry bogs has growers and environmental managers taking notice. Chris Neill of the Woodwell Climate Research Center and his colleagues Rachel Jakuba of the Buzzards Bay Coalition and Casey Kennedy of the US Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Research Service and University of Massachusetts Cranberry Station are investigating how cranberry growing methods and management techniques can ultimately reduce the amount of nitrogen entering Buzzards Bay. Their findings are helping drive decisions by the industry and state regulators about bog management and restoration of retired bogs that bodes well for the environment and the cultural heritage and agricultural economy of cranberry production in the state.

Neill said the group asked itself if they could take a watershed look at what bogs are putting out more nitrogen and what the effect was of their position in the watershed.

“(That would) take into account not only what is coming out of bog bed itself through a structure into a stream channel or a pond, but … the fate of that nitrogen as it works its way down through the whole watershed network all the way down to the estuary.”

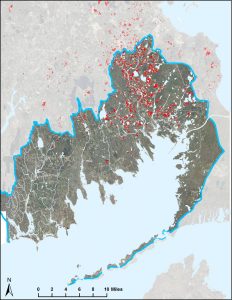

To do it, the team focused on the Wareham and Weweantic River watersheds in Plymouth County in southeastern Massachusetts, areas with the highest density of cranberry farms in the Northeast United States. They developed “a stream network model” that looked at cranberry bog position in the watersheds, their locations relative to groundwater flow and the amount of peat in nearby soils.

The work, he said, is coming at a perfect time for the industry. While production in Massachusetts has inched up slightly or remained stable, many cranberry growers in the state are looking ways of working smarter. Many of growers are looking to retire the traditional “flow-through” style bogs, where rivers run directly through the bog, in favor of more modern growing methods. The flow-through bogs are difficult to maintain, the cultivars are older, yields lower and production costs higher. As it turns out, retiring the “flow-through” bogs makes sense from a nitrogen remediation standpoint as well, says Neill.

“Flow-throughs produce more nitrogen, and tend to be down lower in the watershed where the uptake is less,” explained Neill. He says removing them from the Wareham and Weweantic River watersheds “would reduce the total nitrogen released to the river network by 59 percent and reduce the amount of nitrogen that arrives at the estuary by 45 percent.”

The research project’s dramatic findings were used to help the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration’s newly-created Cranberry Program obtain $10 million in federal funding to work on restoration projects, with the potential for 20 percent of the bogs being restored to wetlands from retirement of flow-throughs, Neill said.

And the Sea Grant network is taking notice of Neill and his co-PIs efforts too. The Sea Grant Association, the non-profit organization dedicated to furthering the Sea Grant program concept, recently awarded the project its annual Research to Application award.

Neill said the award was “totally unexpected” but said it was a tribute to the team and affirmation that their efforts would have a real impact on something that is such an important part of the landscape, cultural heritage and agricultural economy. “There’s an enormous opportunity in southeastern Massachusetts right now,” he said.