Utah Unây: Pooling traditional knowledge and modern robotics

How might we supplement the observations Indigenous communities have been making of the environment over generations with robotic tools? What value might sensor systems, which can sample frequently and at very fine scales, contribute to this rich historical record of our changing climate?

These questions and more were the focus of a weekend workshop for high school-age students from the Mashpee Wampanoag tribe held at WHOI. The workshop underscored how the combination of Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and Western scientific practices can lead to a more complete understanding of an ecosystem.

“Our goal was to show the students that mitigating the impacts of environmental changes across the globe will require both intimate knowledge of local ecosystems and the development of innovative technologies, like robotics,” said Ben Weiss, a WHOI engineer and one of the program facilitators.

The workshop facilitators – from WHOI’s Ladd Thorne Indigenous Knowledge Program (LT-IKP), WHOI Sea Grant and the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe – called the program “Utah Unây.” The phrase loosely translates from the Wampanoag language to “what’s it like?”—a question one would ask when investigating or exploring any natural system or phenomenon.

The free program sponsored five students who gathered on a Saturday morning in July at WHOI's David Center for Ocean Innovation, each with a laptop and box of sensors in front of them. Casey Thornbrugh, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe and consultant with the non-profit Just Collective, set the stage for the workshop, talking to the students about traditional ways of knowing. To illustrate Casey’s message, Dr. Jordan Kennedy, who will soon begin a LT-IKP Postdoctoral Scholar at WHOI, spoke about her research on beaver dams. A member of the Blackfeet Nation, Kennedy described how she incorporated the TEK she learned through conversation and teachings from tribal elders with her academic studies. She described to the students how beavers engineers their structures and build them over multiple generations and wide geographic areas, and discussed how we can learn from them to design robotic systems.

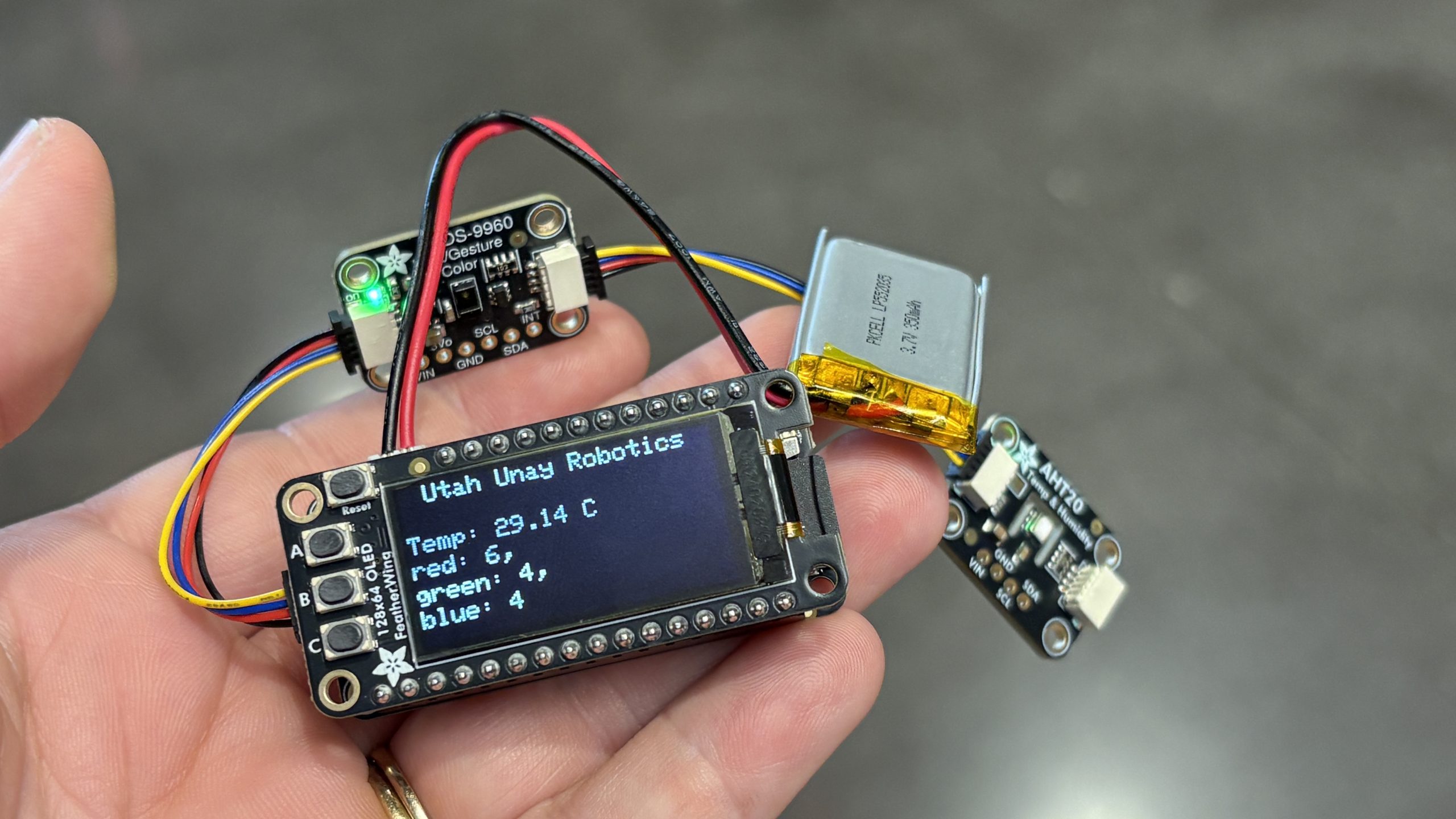

The students soaked up the presentations, but their hands were itching to open up their laptops and start to code. Ben, a robotics engineer, walked the students through connecting their laptops with an Arduino microcontroller—a self-contained, compact computer a little larger than a matchbook that is adept at doing one repetitive task really well—and downloading code to give it commands. With Ben’s instruction, the students were soon connecting sensors to the microcontroller and working with the code to direct sensors to log various environmental signals, like light, temperature, and pressure.

With the workshop based at the David Center, the students also had the opportunity to tour AVAST, WHOI’s Innovation Accelerator, to see how engineers and scientists leverage these resources to go from concept, to prototype, testing, and eventually, deployment of novel technologies in the field.

“The David Center is amazing because students get to see all the spaces, team members, skill sets, and tools needed to take an idea that you have and turn it into something that is ready to put out in the environment,” shares facilitator Grace Simpkins. “From the workspaces, 3-D printer lab, machine shop, test tanks, and more, it inspires innovation!”

Over lunch they chatted with Mashpee Wampanoag Culture Keepers to think about ways that the robotic systems they designed had direct applications to their daily lives.

Ultimately, the students were charged with coming up with a final project, a question they would pursue using the sensor system they developed to gather the data needed to help answer that question. They needed to graph their data and prepare to present their research results during a reception with invited guests including their families.

Over the course of two days, the students programming knowledge grew from learning to make an LED blink to building different sensor systems and testing them in the ocean using waterproof housings. The questions they investigated included how temperature and pressure impact migraine sufferers, how moisture sensors used in the soil can help when growing plants, and exploring how to detect light and color in the ocean. One student, Michael, who works in the estuary with the Tribe, said he looked forward to sharing his new skills: "It really helps a lot with finding information about the waters around you.” When the students presented their final projects, the audience was enthralled and proud, and the students radiated new confidence.

After presenting her project on pressure and color, Misquawahan told the audience her biggest lesson was: “Don’t underestimate yourself because you can do more than what you think you can.”

Another student, Jackson, said, “It looks way more complicated than it actually is. It’s still very complicated don’t get me wrong! But when you’re with the right teacher it’s better understood how to use these.” Other students agreed.

“My biggest takeaway,” said Kuhtah, “is that robotics can help with many different things. There’s an insane range of things you can use it for. There’s no end to what you can do. As long as your brain can think it, you can do it.”

Developing the ability to find technical solutions and work through challenging problems was in many ways one of the main points of the weekend. “This was a far more valuable lesson than any distinct engineering skill we had hoped to teach them," said Ben.

WHOI and the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe hope to continue to work together in the future, leveraging our collective expertise to inspire the next generation and work toward solutions to our environmental needs.