Enjoying Oysters Safely in Massachusetts

Each year, millions of fresh raw oysters are consumed in Massachusetts, most of them in the warm summer months. During that time, aquaculturists in the Commonwealth take extra precautions to safeguard their harvests from the heat, include icing oysters at the time of harvest – a step that can double or triple the weight of the harvest for what some would already consider back breaking work.

Icing oysters is part of a set of requirements the Commonwealth of Massachusetts put in place in 2012 to safeguard consumers after two people who ate oysters fell ill from a bacteria called Vibrio parahaemolyticus. The Massachusetts Vibrio Control Plan includes clear instructions for keeping oysters at or below 45 degrees from the time they are harvested until they are consumed. Keeping them at that temperature prevents Vibrio from reproducing, and keeps them safe to be consumed raw.

“That’s something you can do proactively to arrest bacteria growth – get it on ice and keep it on ice until you get it to the wholesale dealer,” says Diane Murphy, Woods Hole Sea Grant marine specialist. “The wholesaler continues to monitor temperature and keep it at temperature. It’s definitely a way to reduce risk.”

What is Vibrio?

Vibrio is a bacteria that naturally lives in coastal waters. Its presence isn't due to pollution; it can be found in small amounts almost everywhere – in seawater, in mud, in oysters and clams, and lots of other places. Normally, Vibrio levels are too low to cause illness, but in in warmer ocean waters and warmer air temperatures, the bacteria reproduce very quickly. For those who ingest food tainted by high levels of it, Vibrio can cause gastrointestinal problems.

Oyster growers therefore know the care they take harvesting and handling their own oysters is important to keeping consumers safe. And because one incident of Vibrio poisoning can trigger broad oyster-bed closures, the care each grower takes is also important to the livelihood of other growers in the region.

Investigating Vibrio

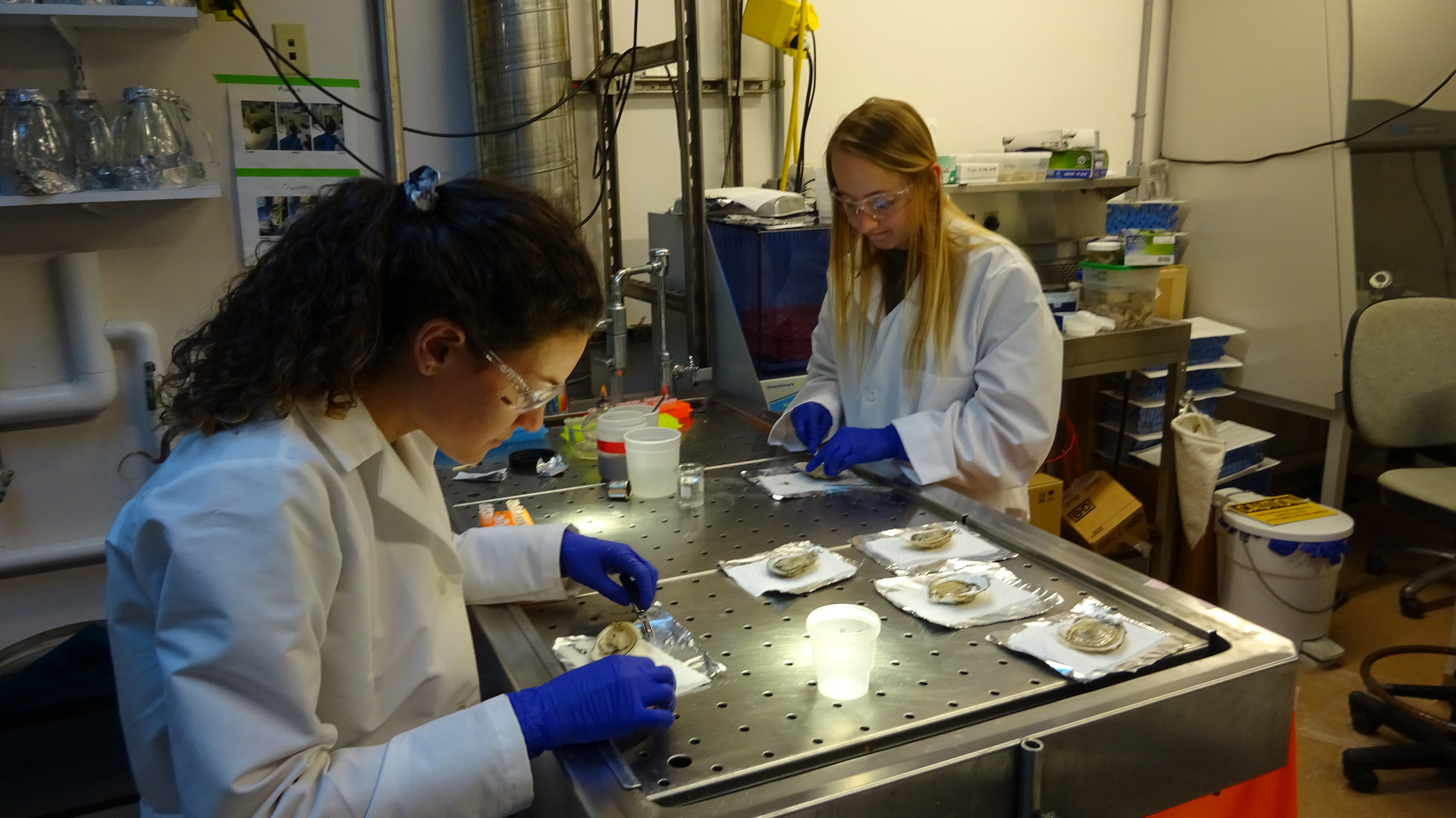

To try to understand how environmental, harvesting and grow-out conditions influence the abundance of Vibrio in oysters, Woods Hole Sea Grant-funded researchers from the Roger Williams University, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Sweet Sound Oysters conducted experiments in two of Massachusetts’s largest oyster-growing regions – Duxbury, on Boston’s south shore, and Wellfleet on Cape Cod.

“Oyster cultivation and harvest practices at these two sites are very different, primarily because of their geographies and tidal characteristics,” says lead researcher Roxanne Smolowitz of Roger Williams University. In Wellfleet the oysters are grown in a shallow, intertidal area, where the water warms quickly. When the tide goes out the oysters are exposed to air for hours; and when the tide comes back in, the water is still warm because it’s coming over the flats. By contrast, in Duxbury the oysters are always submerged in shallow water that is cooler than in Wellfleet.

For the experiment, the researchers studied different oyster growing methods at the sites and then analyzed the harvested oysters using genetic tools. The oysters in Wellfleet were grown in bags above the sediment and in bags on the sediment. The researchers found Vibrio levels were higher in oysters grown above the sediment than the ones that were in bags on the sediment. In Duxbury, the oysters were grown in bags above the sediment and directly on the sediment. The ones on the sediment were not in bags, but were dredged when time to gather samples. In Duxbury, the researchers observed the opposite of what they had found in Wellfleet: in Duxbury the Vibrio concentration was consistently greater in those oysters that were on the bottom as opposed to the ones that were held above the sediment. At both locations, Vibrio abundance in the water column and sediment was consistently very low.

“The study shows that the conditions that can produce higher levels of Vibrio are not always predictable,” says Diane Murphy.

The research team is still analyzing the data, but they have some ideas on what may have caused the difference in Vibrio levels. Smolowitz says in Duxbury, the higher levels in the animals grown directly on the sediment might be due to the harvesting method: “The perturbation of the sediment when the animals were dredged could have increased the Vibrio levels.” In Wellfleet, Smolowitz suspects the findings relate to the animals’ exposure time: “The animals raised in bags above the sediment were out of the water longer, and therefore closed down longer than those raised in bags on the sediment. In warm conditions, Vibrio reproduces very quickly – every 20 minutes, which makes even small differences of exposure time matter.”

There’s more research to be done, and in the meantime the Vibrio Control Plan is helping to keep consumers safe from eating oysters with high levels of Vibrio. Consumers can protect themselves by only eating shellfish from certified dealers and retailers, and making sure they store them under proper refrigeration or ice. Also, says Smolowitz, “People who are immune compromised shouldn’t eat raw shellfish. They become very sick – even when the growers and retailers have properly handled and cooled the shellfish.”